Note: This story first appeared in The 2-Percent Newsletter. I publish stories like this weekly, and most don’t make it onto my website. Sign up here to not miss future stories.

In November of 1944, 36 men entered a lab at the University of Minnesota. They were to be the guinea pigs in one of the most extreme and dangerous studies ever conducted.

World War II was raging. But just as many civilians were dying of starvation as were soldiers in battle. These 36 men volunteered to starve to help scientists understand the effects of starvation and how to bring starving people back from the brink.

In the study, the men were forced to walk at least three miles and do two hours of physical labor every day. During the first 12 weeks, the men ate normally (about 3,200 calories a day). The researchers took baseline measurements of their weight, body fat, resting heart rate, blood panels, strength, psychological state, etc, etc, etc.

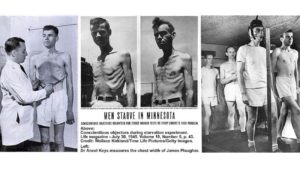

Then the diet was abruptly cut in half, so the guys ate just 1,570 calories a day for 24 weeks straight. They had to keep walking and working and the scientists continued measuring. Check out these photos that show just how profound the changes were from the outside.

What happened to the men internally—both to their bodies and minds—is even more important. The lessons don’t just apply to starving people. They apply to the roughly 50 million Americans who go on a diet each year—and they can tell us everything we need to know about metabolism and why 97 percent of those dieters fail.

This is what happens when we start eating less:

We burn less

As the men began to starve, their resting metabolisms didn’t stay at their normal rates. The men went from burning an average of 1,590 calories a day at rest to just 964. (That’s the same metabolism of a 55-pound child.)

Their bodies saved those calories by doing less of the stuff that kept them healthy. Their heart rates dropped by a third and their body temperatures by three degrees, making them feel freezing cold even in the heat. They stopped replacing cells in their blood, skin, and organs. Their hearts shrank an estimated 17 percent, and they lost 40 percent of their muscle.

What we learned: When we lose weight—by burning more energy than we take in—our bodies pull all kinds of tricks to slow down our burn rate. Our metabolisms eventually adapt and pull us out of a deficit. This sabotages our weight loss and, over time, can make us regain. This is why research shows that people usually hit a weight loss plateau around five weeks.

We move less

When they weren’t doing their forced walks and work, the men radically changed their habits. Instead of being active and engaged with life, they became totally lazy and spent most of their time sitting in bed. Even their minds became lazier. They reported not thinking as clearly, which happened because their brains had dialed back energy use (the brain uses a ton of energy).

What we learned: As we lose weight, our body intervenes to stop the steal by moving less. Our desire to exercise drops and we’re less inclined to, for example, take a walk, get up and down, and fidget (this spontaneous movement can burn hundreds, even thousands of extra calories a day). The most important point is that this all occurs unconsciously. We don’t even realize that we’re moving less in our day-to-day life.

Follow-up research has shown that even if we go to the gym and exercise, our body compensates by secretly moving less. This can almost render our workout moot.

We fixate on food

The participants were ravenous. No shocker there. But they also became completely obsessed with food. Their dreams, thoughts, and conversations revolved around eating. They reported intense cravings and said that the food they did eat was much tastier than it was before the starvation period. A few became preoccupied with recipes. One said that he “stayed up until 5 a.m. last night studying cookbooks.” Many started smoking or constantly chewing gum to curb their food obsession. The researchers finally had to ban gum after one guy was chewing 30 packs of it a day.

What we learned: A hungry brain redirects its mental energy toward food and getting it. No, the average dieter doesn’t stay up until 5 a.m. reading recipes. But he or she likely does, research shows, have more intense cravings and think about food far more often. This is why losing weight isn’t necessarily a matter of willpower. The brain changes in ways that make the pull of food significantly harder to resist.

We feel terrible

The participants were all irritable, depressed, and discontent. They had awful nightmares. One of the men even cut off three of his fingers while operating a saw (he said he wasn’t sure if he did it on purpose).

The guys would watch comedy movies and no one would laugh. When the scientists asked about this, the participants just shrugged and said they didn’t find anything fun anymore. Their reaction to pretty much everything in life was “resignation,” said one of the scientists.

What we learned: We all know being hangry is a thing. As we begin to lose weight, our body reacts by making us more irritable, lethargic, and discontent. Eating more helps us feel better, which incentivizes us to … eat more and regain the weight.

//

The great irony is that all of the effects of starvation are beneficial if a person is actually starving. They helped us save energy and prioritize food back when food was harder to come by (long before we found ourselves in a world of stocked pantries and fast food on every corner).

Today, however, these survival mechanisms are working against us. They’re why so many of the 72 percent of Americans who are overweight or obese struggle to lose weight. Dieters start with enthusiasm and a normal metabolism. Then they start to drop weight and their body sabotages their efforts.

I became interested in this topic after spending a month in the Alaskan wilderness while reporting my book, The Comfort Crisis. We packed in roughly 2,000 calories a day but we were burning far more than that, thanks to carrying 90 pounds packs across rough terrain all day. My mind and body went to places just like the guys in the experiment, and I left the wild 10 pounds lighter.

After I returned from Alaska, I traveled to hang out with my friend Trevor Kashey, a Ph.D. biochemist. He’s developed methods that help people face the harsh realities of weight loss. He’s built a tribe of three-percenters, that tiny fraction of people who manage to lose weight and keep it off. His methods harness our evolutionary adaptations rather than fight against them, and they’re featured in The Comfort Crisis.